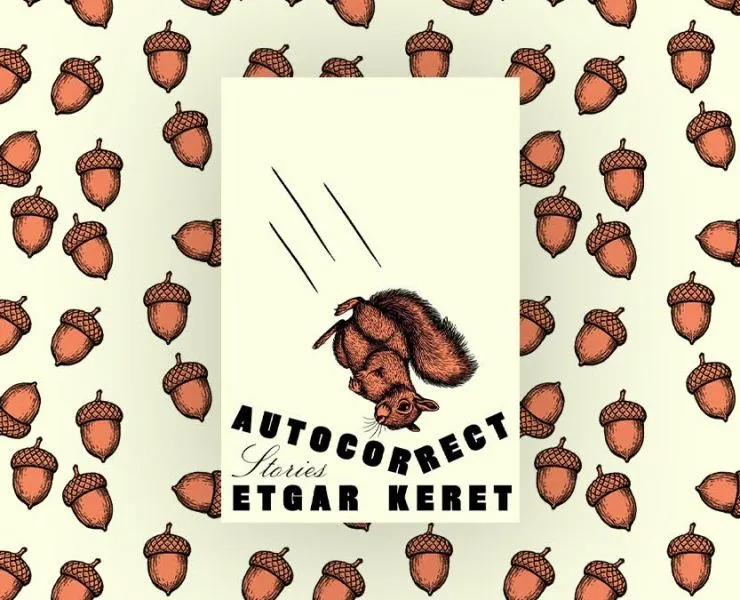

Harold Bloom once noted that the twentieth century’s greatest writers often leaned atheist or agnostic, a reflection not just of their craft but of Western society’s broader drift. The World Wars, those cataclysms that mocked Enlightenment ideals and rationalism, shattered faith in a virtuous cosmic core. As a writer drawn to stories that probe the human condition, I found these ideas swirling through my mind while reading Etgar Keret’s Autocorrect, a collection of short stories that dances on the edge of dark comedy, refusing the comfort of cosmic justice.

Keret, an Israeli maestro of literature and film, crafts tales that resonate in over forty languages, gracing pages of The New Yorker and Le Monde, earning accolades, and teaching at Ben-Gurion University. His Substack newsletter, Alphabet Soup, hums with his wry voice. In Autocorrect, he sharpens the subtlety of his earlier work, like The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God. Where Bus Driver spun a sprawling tale of an afterlife for suicides, debating its mechanics, Autocorrect’s “Present Perfect” offers a fleeting glimpse of a spectral waiting line, unresolved and haunting. This shift feels deliberate—a weariness of grand metaphysics, a pivot to human bonds as the truest anchor, whether on Earth or beyond.

The stories pulse with relationships: lovers, parents, children. “Soulo” is a gem, tracing a couple’s unraveling marriage as both turn to AI companions. The interplay among the four—human and machine—is sharp, funny, and meticulously causal, a mirror to love’s absurdities. “Earthquake” stings with the quiet tragedy of a man’s passivity, letting a great love slip away. I lingered over these moments, struck by Keret’s ability to distill complex emotions into swift, vivid strokes. As a writer, I admired his economy, each word a pebble rippling across the story’s surface.

Some tales echo Borges’ labyrinthine musings. In “Director’s Cut,” a filmmaker pours seventy-three years into a single movie, watched only by a baby born during its screening. Others, like “Mitzvah” and “Intention,” recall Hasidic parables, with protagonists caught in prayer and enigmatic aftermaths. Yet, unlike those mystic tales, Keret’s stories shrug off divine clarity. “Mitzvah,” with its near-random cascade of events, sparked thoughts of a universe indifferent to our spiritual striving—a world where meaning emerges not from gods but from chance and connection.

What sets Autocorrect apart is its rejection of karma’s tidy balance. Dark comedy often leans on justice—cruelty begets consequence—but Keret’s world is messier. Evil or unkindness may go unpunished, and goodness unrewarded, mirroring life’s ambiguity. This refusal to moralize captivated me, as a reader who cherishes stories that trust us to grapple with uncertainty. The humor, mordant and surprising, cuts through the weight, making the collection as entertaining as it is profound.

Keret’s prose is a marvel, swift yet layered, each story a prism refracting human truths. I found myself rereading passages, savoring their clarity and depth. For readers of literary fiction, dark comedy, or translated works, Autocorrect is a treasure. It’s a book that lingers, not with answers but with questions—about love, loss, and the stories we tell to make sense of a world that defies sense. As a blogger, I’d urge you to read it in a quiet corner, letting its insights unfold like a conversation with an old friend.