What do I remember? Of myself? Of my mother? Of myself as a mother? The questions drift like leaves caught in an autumn gust, spiraling, never quite landing. They linger in the artifacts I hold—photographs yellowed at the edges, diary pages creased with time, poems scrawled in moments of fleeting clarity. Yet, what slips through the cracks of these relics? What is lost in the act of rendering experience into something tangible? How do I bridge the chasm between the image and its truth, between the self I am and the other I long to know?

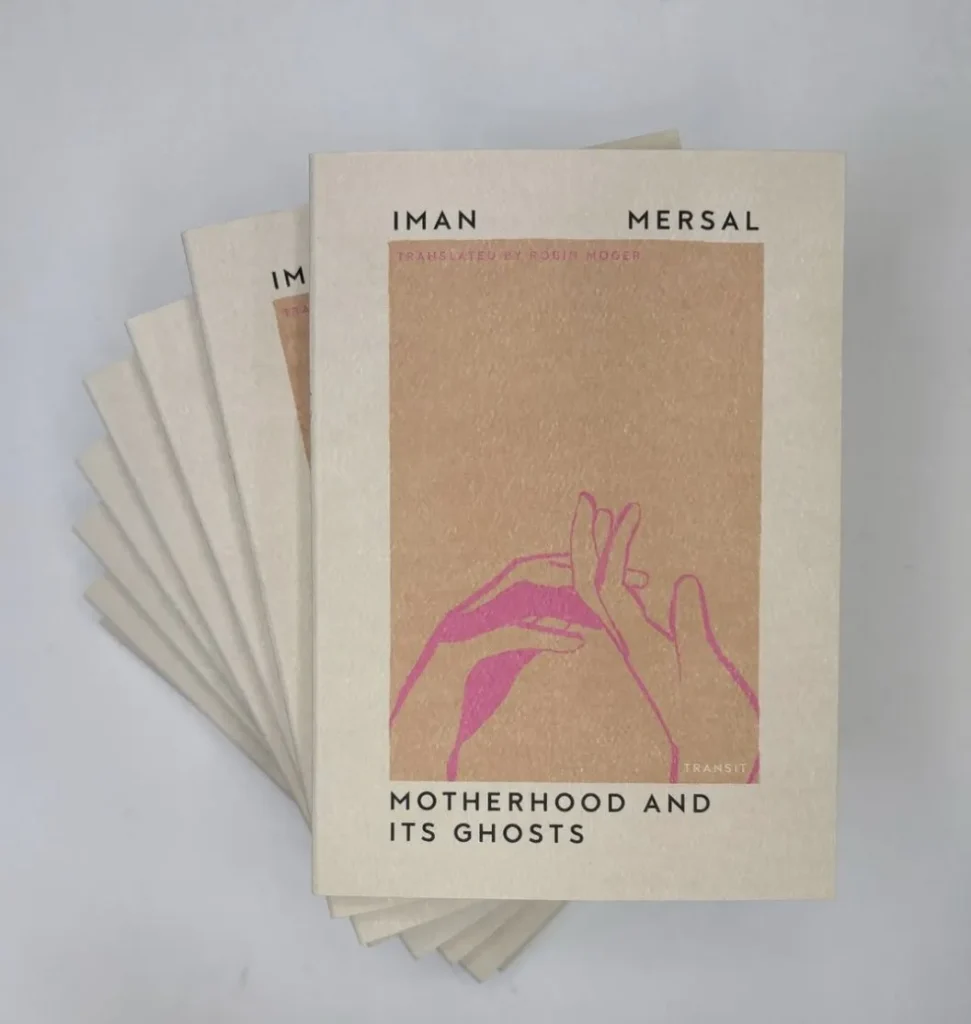

I sit with these questions, not to answer them but to let them bloom, wild and untamed, in the garden of my mind. Motherhood, I have learned, is no straight path. It is a mosaic of fragments, a tapestry woven from interruptions, from moments of piercing clarity and others shrouded in fog. I think of Iman Mersal’s Motherhood and Its Ghosts, a work that dances between prose and poetry, analysis and confession, as if to mirror the fractured beauty of memory itself. Like her, I find no solace in smoothing the jagged edges of maternal experience. Instead, I embrace the disruptions—the sudden wail of a child, the weight of grief, the fleeting joy of a shared laugh—as the very threads that stitch my identity together.

I am a mother, but I am also a daughter, forever tethered to the ghost of my own mother. She was twenty-seven when she left this world, her life extinguished as mine began. I carry a single photograph of her, its edges soft from years of touch. In it, she gazes at something beyond the frame, her eyes alight with a secret I will never know. Her hair is woven into a braid, thick and dark, a rope I imagine anchoring her to the earth. Yet the photograph is a lie, or perhaps a half-truth. It captures a moment, yes, but it cannot hold the warmth of her voice, the rhythm of her breath, the life that pulsed within her. She is a ghost in this image, both present and impossibly distant.

I turn to this photograph often, not to find her but to find myself. I am not the child she held, nor the mother she was. I am the space between, the liminal thread that binds us. Mersal writes of this in-betweenness, this refusal to be contained by the frame. “You are the relationship that links you both,” she says, “the relationship that is erased or hidden or even excluded from the picture itself.” I feel this truth in my bones. Motherhood is not a role to be played or a story to be told. It is a living, breathing connection, one that defies the neat boundaries of representation.

In my own mothering, I am pulled in a thousand directions. The practical demands of caregiving—diapers, meals, bedtime stories—fragment my attention, scattering my thoughts like seeds in the wind. Yet, within these interruptions, I find meaning. The act of tending to my child, of holding her hand as she stumbles toward sleep, is not a distraction from understanding motherhood but its essence. Like memory, which unfolds in fits and starts, mothering demands that I be present in the chaos, that I weave coherence from the threads of disruption.

I think of the poets Mersal invokes—Anna Swir, Adrienne Rich—whose words cut through the haze of archetype to reveal the raw, ambivalent heart of maternal love. I think, too, of Ryoko Uemura’s photographs, capturing the tender act of bathing her dying daughter, and of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, their silent protests a testament to loss and resilience. These images, these stories, are not answers but mirrors, reflecting the myriad ways motherhood resists definition. They remind me that to mother is to be both anchored and adrift, to hold love and grief in the same trembling hands.

My own narrative is no less fragmented. I recall the early days of motherhood, when exhaustion painted the world in shades of gray. I remember the fierce love that surged through me, tempered by moments of doubt, of wondering whether I was enough. I carry, too, the weight of my mother’s absence, a shadow that lingers in every milestone my child reaches. How I wish she could see her granddaughter’s first steps, hear her laughter, know the woman I have become. Yet her absence is not a void but a presence, a haunting that shapes the way I love, the way I remember.

Memory, like motherhood, is not a static thing. It is a garden, one that demands tending. Mersal speaks of watering memories as one would flowers, of maintaining contact with the witnesses of the past. I take this to heart. I write letters to my mother, though she will never read them. I tell my daughter stories of her grandmother, weaving her into the fabric of our lives. I revisit the photograph, not to fix her image in my mind but to let it shift, to let it breathe. In this tending, I find not certainty but possibility, the hope that memory, like a bulb planted in autumn, might bloom come spring.

There is freedom in this incompleteness. The archetypes of motherhood—the saintly Madonna, the selfless nurturer—cannot contain the fullness of who we are. We are too much, too vast, too contradictory. We are the love that spills over, the grief that lingers, the moments of joy that flare and fade. We are the ghosts we carry and the legacies we leave. To mother is to inhabit this liminality, to embrace the dissonance between the self we present and the self we feel.

I return to the photograph, to the woman who is and is not my mother. I see her not as a fixed point but as a constellation, a gathering of light and shadow. I see myself, too, in the spaces beyond the frame—the mother I am, the daughter I remain. And I see my daughter, her future unwritten, her story intertwined with ours. We are not whole, not in the way photographs or poems or memories might suggest. We are fragments, beautifully broken, pieced together by love, by loss, by the act of remembering.

In this garden of ghosts, I walk with them all—my mother, my child, myself. I tend to the memories, to the relationships that bind us. I let the questions linger, unanswered, for they are the roots from which understanding grows. What do I remember? Not everything, not enough. But I remember the weight of my mother’s braid, the warmth of my daughter’s hand, the ache of love that ties us across time. And in that remembering, I find not answers but a song, soft and eternal, singing of motherhood, of ghosts, of me.